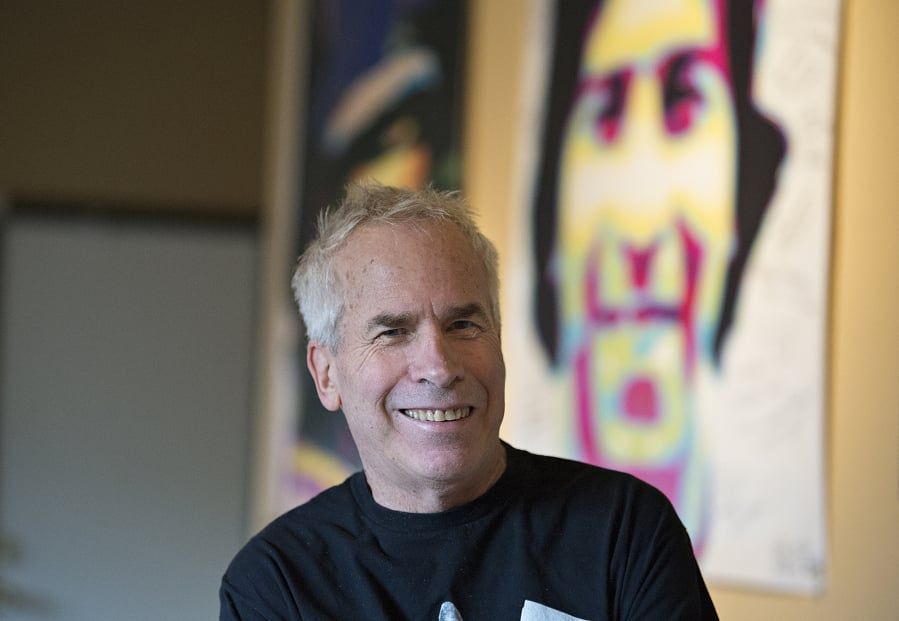

“Jazz Organist Louis Pain Plays On Washougal resident and acclaimed musician releases new CD with band, works to return to performing after suffering heart attack in March By Scott Hewitt, Columbian Arts & Features Reporter Photos by Amanda Cowan Published: May 9, 2019 WASHOUGAL — Maybe it was the pneumonia that hit organist Louis Pain a few weeks before the big gig. Maybe it was the unrelenting pressure of pushing his trio’s new, hourlong album toward release by deadline. Or maybe it was the french fries. “I sat there thinking, I knew I shouldn’t have eaten those f—g french fries,” said Pain, 66. Whatever the cause, Pain found himself in unexpected pain one night in late March when he was onstage in Portland’s Pearl District, jamming away with his trio. There were about 20 minutes left in the set when Pain felt what seemed like sudden heartburn. “It wasn’t like Fred Sanford, ‘This is the big one!’,” Pain says. He finished the tune. He went outside and sat down, feeling queasy. Somebody checked his pulse and found it irregular. Pain’s wife, Tracy, stuffed him into their car and raced to PeaceHealth Southwest Medical Center in Vancouver. He walked into the hospital and politely asked to jump the emergency department line because he might be having a heart attack; as soon as he said those words, “heart attack,” he felt like a racing car that pulls into the pit and is immediately descended upon from all directions by a fast-working crew. The crew at PeaceHealth did a great job, he said, determining that he was indeed suffering a heart attack and quickly inserting two stents. Pain was told later that one of his arteries had been 100 percent blocked. It was the kind of heart attack doctors call a widow-maker, he said. Tracy, meanwhile, was asked if she wanted a chaplain to sit with her. “This has been much tougher on her than on me,” Pain said. Pain learned that heart disease and its causes aren’t completely understood. A slender guy with low blood pressure, Pain used to think he was about as low-risk as you could get; but just being a male over 60 years old means that’s no longer true — obviously, he said.“I got lucky,” he said. “Tracy saved my life.” Heavy Pain grew up in an artistic San Francisco family that was deep into literature and hosted celebrity poets; he said Allen Ginsberg and Robert Bly once brawled at his house. Pain loved to write, too, but when he heard the humongous sound of the Hammond B-3 organ swirling through a rotating Leslie speaker — on The Animals’ classic cry of soul, “The House of the Rising Sun,” and Bay Area great Leon Patillo playing a version of the grand “2001: A Space Odyssey” theme — he was electrified. “The sound was so compressed, I just had the idea that this was something really, really cool,” Pain said. Pain’s mother, feminist poet Frances Jaffer, was the one who signed him up for lessons (and is the inspiration for the CDs opening song, “Frances J”). Pain excelled at the complex, distinctive Hammond B-3, and he gigged for years in the Bay Area. He was usually the only white guy in the band, he said. But that life wore him down — the stress, the ubiquitous substance abuse, the showbiz dishonesty — so in his early 30s he moved to Portland, enrolled in college and studied history. He took a corporate editing job and quickly came to hate it, so Pain accepted a bass player friend’s invitation to fill an empty slot in the Paul deLay Band. “It’s where I belonged all along,” Pain realized, and he’s been playing music ever since — mostly with local stars like Curtis Salgado, Mel Brown, Linda Hornbuckle, LaRhonda Steele and the late Paul deLay, but increasingly as the leader of his own King Louie Organ Trio. He played an estimated 1,500 times at Jimmy Mak’s jazz club before it closed in 2016, and he’s been a regular at Portland’s annual Waterfront Blues Festival. Until about 20 years ago, Pain said, he used to lug all 250 pounds of his gargantuan Hammond B-3, plus 125 more pounds of Leslie speaker, to every gig. Nowadays, he said, his live weapon of choice is a handy electronic keyboard that weighs a few dozen pounds — but the swirling sound of the Leslie speaker is non-negotiable, Pain said. Also non-negotiable: From now on, Tracy said, they’re hiring someone anytime her husband needs to move heavy equipment to a gig. All stars Pain hates to back out of commitments, but he’s had to cancel numerous gigs, lessons, etc. lately. His heart attack has resulted in a serious financial hit for the couple, they said. They’re “grateful for the outpouring of love, prayers and support from our friends and family but especially from those from our hometown here in Washougal,” Tracy posted on social media recently. “Neighbors who’ve been helping us mow our lawn, bringing over food, making store runs … offering to help with his heavy equipment. We thank you!” You can show some love at two upcoming Pain performances. The King Louie Organ Trio celebrates its new CD release, “It’s About Time,” Friday at the Salud Wine Bar in Camas; on June 2, the Crystal Ballroom in Portland hosts an all-star benefit for Pain (and for The Caring Ambassadors, a nonprofit health-screening and health research organization) featuring talents like Brown, Salgado, Bernard Purdie, My Happy Pill and many more. Pain will play during that concert, he confirmed. About time Louis and Tracy Pain moved to a Washougal hillside about 10 years ago, and immediately worried that their neighbors would start calling the police about the decibels pouring out of their big garage during rehearsals. But when they checked, they said, their neighbors were pulling up lawn chairs to listen, and suggesting that the band open some windows to let the music out.A couple of years ago, Louis Pain said, song inspirations started coming to him about as fast as he could jot them down. He wound up writing 11 instrumental numbers; when fans remembered and requested them, he and his wife realized they deserved to be recorded. He gratefully accepted an offer of free time at a friend’s new studio in Portland, and musically the project was nothing but a delight — but it also had more than its share of technical and logistical hiccups that slowed things down and stressed Pain out, he said. The finished CD got delivered to its release party in Portland with minutes to spare. The title of the CD, “It’s About Time,” was intended to convey that three longtime Portland jazz-scene sidemen were grabbing some well-deserved limelight at last: saxophonist Renato Caranto (who’s played with everyone from Merle Haggard to Esperanza Spalding), drummer Edwin Coleman III (who’s played with Charles Neville of the Neville Brothers), and bandleader Pain on the Hammond B-3. (Other musical luminaries who guest-star on the album include drummer Brown and Tower of Power guitarist Bruce Conte, who mailed in some guitar overdubs from overseas.) But, post-heart attack, “It’s About Time” seems to suggest something even deeper about life. “I really did put blood, sweat and tears into it,” Pain said. “I guess it literally just about killed me.”” - Scott Hewitt

“Louis Pain Soulful Spontaneity on the B-3 The scene: San Francisco, California, sometime in the mid-sixties. A young Louis Pain, the future Hammond B-3 organ phenomenon, is at a restaurant with his family. A rock song begins to play on the jukebox, and Louis’ big brothers, five and seven years older than him, rush over to hear the music better. Louis follows, fascinated as always by whatever fascinates his big brothers. They lean into the speakers and soak in the sound of the instrument that holds them spellbound. “Listen,” they say to young Louis. “Listen to that organ!” “I couldn’t hear it,” Pain says today. “I couldn’t pick out the organ.” If you were expecting some inspiring story of a musical epiphany, well, apparently it just wasn’t yet time for Louis Pain’s moment of enlightenment. But clearly he saw the light eventually – otherwise you wouldn’t know him today as one of Portland’s most accomplished and expressive practitioners of the Hammond B-3 art. The Hammond organ is an instrument that truly occupies a class of its own, and playing it successfully requires years of dedication, an innate sense of musicality and tone colors, and of course a willingness to lug something about as awkward and heavy as a commercial refrigerator to every gig you play. Pain has proven himself to be more than adequate to the challenge through his remarkable 10-year stint with the Paul deLay Band; his irresistibly funky soul-jazz gig with Mel Brown at Jimmy Mak’s, still going strong after eight years; his tasty Purdie Good Cookin’ project with the revered drummer Bernard Purdie and a host of Portland all-stars; and now his rise to bandleader status with his King Louie & Baby James group, featuring the soul-drenched vocals of “Sweet Baby James” Benton. September saw the release of their first CD, an essential live recording of their head-turning performance at the 2005 Waterfront Blues Festival. Pain is obviously thrilled with his latest musical venture. “Working with Baby James is great,” he says. “I mean, he’s so soulful. I’ve worked with some soulful singers in the Northwest, but I do think he’s special.” In addition to Pain and Benton, the band features Paul deLay Band and DK4 stalwart Peter Dammann on guitar, the young but remarkably solid Anthony Jones on drums, and local saxophone standout Renato Caranto. Pain provides the bass in old-school fashion, putting his left hand and foot to work on the B-3. Janice Scroggins adds piano as a featured guest on the live recording, and appears with the band occasionally as well. Audiences are responding enthusiastically to their performances, and Pain is very excited about the group’s possibilities. So after his inauspicious start at the jukebox, how did Louis Pain come to be such a widely-recognized master of the Hammond organ? Back in mid-sixties San Francisco, Pain’s brothers continued their fascination with the sound of the organ. Happily, he did eventually develop an ear for picking out that sound on records, and he began to appreciate the animated touch an organ added to the arrangements. Finally, when he witnessed the cool vibe exuded by the Hammond player in his brother Duncan’s band – “picture Curtis Mayfield sitting behind a Hammond,” says Pain – that sealed the deal. He began to make noises to his parents about wanting to learn to play the Hammond organ. Soon his mother, a classical pianist, surprised him by signing him up for lessons with a local organist. “I was fortunate to have parents who supported my musical ambitions from day one,” Pain says. The teacher was Norm Bellas, who still plays actively in the Seattle area. His instructional approach was somewhat unusual, but it seemed to work for the young Pain. “Norm’s method was to immediately get you improvising blues,” Pain remembers. “Before you learned a C major scale or a chord, you were improvising blues. He gave all his students a 12-bar blues progression and a repeating bass line, and a set of chord voicings to play with that bass line. And once you started to get that down, he’d give you three notes you were allowed to use over each chord in improvising. He would insist that you ‘tell a story’ with those three notes. And if you deviated from those three notes he would grab your hand and stop you. Or if you played anything that he said was not coherent, he would stop you and say, ‘That’s not logical.’ He’d stop you cold.” This disciplined style of instruction seemed to be just what Pain needed; he studied with Bellas for two years, and made great strides in his playing. As a late starter at 16, he could barely manage “Chopsticks” – suddenly at age 18 he was playing at jams and joining bands. “Pretty soon I started playing in a Top 40 band,” Pain recalls. “Top 40 wasn’t that bad in those days. A lot of the tunes were kind of bluesy, and there was improvisation, you took solos, there were no drum machines. We played at a club called the Cock’s Inn – that was my first gig. And I’m sure the band was terrible, but it was a great experience for me.” Around the same time, Pain experienced the musical epiphany that had eluded him so much earlier. Initially, his goal at the organ had been to play like Booker T. Jones, whose music his brother Duncan had introduced him to along the way. But one evening he found himself stuck alone in someone else’s house for the night, and upon searching for some music to listen to, he found nothing but jazz records. He eventually chose Art Farmer’s Live At The Half Note and put it on, expecting it to serve simply as background music. Instead, it was an ear-opening experience. “They did ‘Stompin’ At The Savoy’ – this long, hard-swinging, swing blues,” Pain says. “And I thought, this is the coolest, hippest…I get it! I’d never liked jazz, but this one night, I heard it with new ears. Afterwards, when I heard people like Jimmy Smith, Jack McDuff, Jimmy McGriff, playing that walking bass line, like what I’d heard on that Art Farmer record, I said, ‘I get it. Oh, that’s cool. I like that.’ And I started listening to a lot of those people.” Soon Pain found another source of inspiration in local jazz organist Chester Thompson, “who was playing this black neighborhood jazz club,” Pain remembers. “That club was within walking distance of my house; it was called the Off-Plaza. I used to walk down there on weekends, and they would back up touring singers, sometimes horn players. I heard Irma Thomas with him, other people. It was a small club, but they had talented artists coming through there. Chester’s trio accompanied them, and he was fantastic – I mean, incredible. And with a couple exceptions, I’d never seen anyone play jazz organ before; I’d really just heard it on records. And here I’m seeing this guy that’s as good as anyone I’ve heard, right up close in a neighborhood club. To this day I haven’t heard anyone do some of the things that Chester did. Joey DeFrancesco is an incredible organ player, and does things that I haven’t heard anyone else do, but Chester is in that same league.” In later years, Thompson went on to play with Tower Of Power and Santana. Now Pain aspired to build his organ skills to emulate the swinging, grooving, bluesy style of playing that he heard in such artists as Thompson, Smith, McDuff and McGriff. He continued playing with that first Top 40 band for about two years, then began playing in a string of what he calls “second-rate soul bands.” This was a period of time in Pain’s life when he was “usually the only white guy in the band…and often the only white guy in the club. But even in the roughest clubs, if anyone did mess with me, another patron would say, ‘Leave that white boy alone – he’s in here to play music for you!’ It was like having diplomatic immunity.” During this period of intensive dues-paying, Pain used his time well by continuing to sharpen his organ chops and seizing the opportunity to share stages with the likes of Luther Tucker, vocalist Little Frankie Lee, lap steel guitarist Freddie Roulette and Marvin Holmes & The Uptights, a popular Bay Area soul band. He surrounded himself with musical excellence, even sharing an apartment with guitarist Bruce Conte, who would go on to join Tower Of Power. Pain says that during this period he also fell under the influence of gospel music, spending countless hours listening to James Cleveland, Billy Preston and others. With time, his musicianship had improved to such a level that he “graduated” to playing with Jules Broussard, a Bay Area saxophonist with an impressive track record. Broussard had replaced Fathead Newman in Ray Charles’ band, and he also played and recorded with Boz Scaggs, Van Morrison, Carlos Santana, Elvin Bishop, Art Garfunkel and many others. Pain compares the style of Broussard’s group to what he does today in Mel Brown’s B-3 Organ Group, including the seamless transitions from one song to another without stopping. “While we were finishing one tune he’d be stomping off the next tune and yelling the title at us. The alumni from his band called him ‘The General.’” “But it was really an apprenticeship,” Pain says. Over his nearly ten years with Broussard, Pain worked his way through Horace Silver charts, Charlie Parker, Art Blakey, and many jazz standards. To keep the mix interesting and clubgoers dancing, they also spiced up the repertoire with pop and Motown material – even an occasional romp through the disco hit “Fly Robin Fly.” In addition to the musical grounding he provided, Broussard also planted a seed with Pain by mentioning a trip he’d taken to Portland, Oregon and the vibrant, welcoming music scene he’d found up there. Pain eventually moved on from Broussard’s band, and soon was playing in a Top 40 cover band called Hot Street with his former roommate Bruce Conte, who had left Tower Of Power. It was a solid band made up of skilled players, but as this was the early 1980s, the repertoire consisted largely of hits by artists like Michael Jackson, Olivia Newton-John and Foreigner. “Oh, it was miserable,” Pain recalls. “And I still wanted to play the Hammond, and I was told, ‘Man, that’s a white elephant. No one wants to hear a Hammond organ anymore.’ So I was playing synthesizers, and I really hated that.” For a Hammond B-3 aficionado, a purely electronic synthesizer – particularly the types that were available then – is a decidedly uninviting musical partner. “It’s like looking in a dead fish’s eye,” Pain says with distaste. “There’s no life. It’s not animated. You just can’t breathe any life into that. The ironic thing was that you went around hearing bands with synthesizers in them, and the keyboard players spent most of their time playing simulated organ sounds on those things. Terrible, sniveling Hammond imitations. That’s what you ended up playing on the damn things: terrible imitations of what a Hammond does so well.” Pain endured the challenges of Hot Street – mandatory synthesizers, uninspiring repertoire, exhausting road work and bandmates’ drug problems – for a few years, but ultimately he reached a crossroads at which he started to wonder what his life would have been like had he pursued a different early interest: journalism. He had always enjoyed writing, and had won awards for his efforts in high school. When his grandparents heard of his potential new direction, they offered to provide an allowance that would let him return to school and get a journalism degree. Since the amount they offered wouldn’t get him far in the Bay Area, Pain decided in 1986 to go north to Portland and attend Portland State University. Despite the fact that the school discontinued its journalism program before Pain ever took his first class, he persevered and studied hard, earning a degree in history with high honors and winning a historical writing award. Louis Pain’s non-musical career was short-lived, however. Not long after graduating from PSU, he felt the distinctive pull of music once again. He found that his time away had caused him to appreciate the positive side of playing music for a living – “the incredible lift and emotional release you get from the playing,” as he puts it. When he realized how much he missed that aspect, he decided to look at the negative elements he’d endured in the past as necessary evils of doing what he loved. The fact that he found himself in the Portland music scene that Jules Broussard had spoken of so glowingly was a happy coincidence. Through a golfing buddy who was playing bass with the Paul deLay Band, Pain got word that their keyboard player had left and the slot was open. Since deLay had just been arrested on federal drug charges and would likely be serving time soon, it looked like an opportunity for a short stint that would allow Pain to ease gently back into the music scene. An additional motivation was the fact that Pain’s “college fund” had run out, and he needed work of some kind. So in 1990, Pain joined up and began to meld his R&B- and jazz-inflected Hammond licks with Paul deLay’s distinct songwriting voice and innovative harp playing. As Pain puts it, “My thing musically has always been to listen to what’s happening around me, and to try to play something that’ll make it work better. My goal is that after I’ve joined a band, it’ll sound better than it did before.” This was certainly true for the Paul deLay Band. The deLay albums on which Pain appears are widely regarded as the band’s best. And as it turned out, they had the opportunity to get two albums in the can (The Other One and Paulzilla) during the three years of legal wrangling that preceded deLay’s incarceration – or “writing sabbatical,” as he’s been known to refer to it. Also new to the band when Pain joined was saxophonist Dan Fincher. “Dan and I entered that band at the same time, and I think the combination of the two of us coming to the band really changed it,” Pain reflects. “We both came from a background of playing more R&B, where there were parts, and parts that worked together, and we were both listening for those parts. And I had played a lot in a band with one horn before, where the organ combined with that horn became a horn section.” This synergy between saxophone and organ became a trademark aspect of the Paul deLay Band’s sound. Soon, with all band members filtering ideas through deLay, whose own influences range “from Chicago-style blues to Lawrence Welk,” according to Pain, the Paul deLay Band really blossomed. While the short stint Pain had envisioned upon joining the band turned out to be anything but, one might have expected the gig to end once deLay entered a minimum-security prison for his 42-month sentence. This was not to be, however, as the band decided to continue playing with Linda Hornbuckle out in front, billing itself as the No deLay Band. They released a memorable record with this lineup, which featured Hornbuckle holding forth soulfully over innovative reworkings of chestnuts like “I Can’t Stop The Rain,” “Hound Dog,” and even a nod to deLay himself with a driving version of his own “I Can’t Stop.” When Paul deLay emerged from his prison term, it was clear that he had indeed been writing. He was ready to resume working with his band, with an album’s worth of studio-ready songs in his back pocket. “He’d had three years in prison with nothing to do but think about these tunes,” Pain remembers. “Paul had a prison band mainly made up of beginners, so he had them learn their parts note-by-note – these parts he had in his head, one note at a time. He called them the American Standard Blues Band, after the toilets they have in the joint! And he somehow managed to get a cassette recording of them playing these tunes. So when he came out, he had a little recording of these tunes – badly played, but there they were, already fleshed out.” Those songs became the foundation of 1996’s Ocean Of Tears, which Pain believes is the deLay Band’s strongest album. Mixing songs of loss, regret and recovery with raucous celebrations of love and triumph, deLay had indeed concocted a potent musical formula. “These tunes were, for the most part, complete compositions,” Pain says. “We worked with Paul and helped him arrange them, but basically these tunes were ready – they were the result of three years of thought. And so I think that’s a really cool record. I think we did a good record there.” The Paul deLay Band was back on track, and blues fans welcomed them back enthusiastically for local, national and international appearances. Paul continued to write compellingly and collaborate with the band for two more highly-regarded albums, Nice & Strong and Heavy Rotation. The latter was notable for its lack of a bassist, with Louis Pain ably handling those duties on the B-3. While the success and acclaim for the deLay Band was welcome, Pain eventually began to miss the soul-jazz organ style in which he’d played for so long before coming to Portland. In his spare time he began to explore the possibilities of working in that style, and he briefly put a band together with drummer Tom Royer that played Monday nights at the Gemini Pub in Lake Oswego and featured Dan Faehnle, Patrick Lamb and Curtis Salgado. Despite the all-star lineup (in fact, the group was called the Blue Monday All-Stars), it failed to attract much of a following. Before the group folded, however, local drum idol Mel Brown dropped in and heard them one Monday night. Months later, he called Pain. “It had always been one of my dreams to play with Mel Brown,” Pain says. “Because I had heard him and Leroy Vinnegar and Dan Faehnle and Thara Memory playing at Jazz de Opus and thought, ‘Way cool.’ And I’d wondered if these guys liked organ or not…I just wondered, I didn’t know. So Mel calls me up and we get to talking, and it turns out he’d started out playing with organ groups, and had even played with Jules Broussard during a period when Mel had lived in the Bay Area.” With that, the Mel Brown B-3 Organ Group was formed, its lineup including Thara Memory, Dan Faehnle and Renato Caranto. Initially they played Tuesday nights at Berbati’s Pan. According to Pain, however, that venue didn’t quite work for them; but “Jimmy Mak had this new club and got us in there playing Thursdays, and after a while that took off and we’ve been there eight years now.” Pain’s work with Mel Brown started while he was still with the deLay Band, and he managed the occasional schedule conflict by having Glenn Holstrom (Hammond B-3 player with Lloyd Jones) fill in for him when he was out on the road. But other musical opportunities continued to arise for him, including a collaboration with one of his idols, drummer Bernard Purdie. The association with Purdie dates back to the No deLay Band days, when Purdie showed up at a jam the band was hosting and sat in. “Everybody had a ball,” according to Pain, and that started him thinking about the possibility of playing with Purdie in some kind of organ group lineup. Guitarist Jay “Bird” Koder actually put together a few gigs like that, which were successful and enjoyable. Eventually Purdie was tossing around the idea of producing a live recording based around a theme. Purdie and his manager Aase Otto got together with Pain and his wife Tracy (a frequent collaborator and key supporter), and they decided to use food and cooking as a unifying concept for the live album. Tracy Pain came up with the title Purdie Good Cookin’, and the project was underway. With tasty song suggestions from KBOO’s Tom Wendt and legendary local DJ Pat Pattee, as well as original tunes from Pain, Koder and trumpeter Thara Memory, the set list took shape. The players were assembled: Purdie, Pain, Koder, Memory, Linda Hornbuckle on vocals, Renato Caranto on saxophone, and special guest Rob Paparozzi on harmonica and vocals. There was only a single rehearsal before the performance took place at Jimmy Mak’s. “An interesting thing happened in rehearsal,” Pain recalls. “I was trying to chart out some of these arrangements, and Thara was sort of resisting that. And he said, ‘What, are you afraid something might happen?’ In other words, that some spontaneity might accidentally inject itself into this project! The irony of that is that in most of the groups I play in, I’m usually the one wishing for more spontaneity, but playing with Thara and Bernard, I was the one who was the stick in the mud. … But Thara was right, you know? And more and more, that’s what I’m enjoying in playing, is not having things arranged.” The Purdie Good Cookin’ disc, released in 2003, was a resounding success. Just as the song titles lead the listener through a culinary smorgasbord, the music offers a delectable assortment of musical styles. There’s the classic opener, “Memphis Soul Stew”; the uptempo blues of “Kidney Stew Blues”; the irresistible grooves of “Red Beans & Rice” and “A Little Soul Food”; and the urgent manifesto of “Givin’ Up Food For Funk.” The masterful beats of Purdie, often billed as the world’s most recorded drummer, combine with Pain’s infectiously funky bass lines and syncopated chord punctuations to form a rock-solid foundation that allows each song to soar. Pain relishes his musical experiences with both of these powerhouse drummers. “Bernard Purdie is like a force of nature,” Pain says. “There’s no one like him; he’s unique. When you get onstage and play with him, it’s like ‘Oh my God.’ It feels like this guy is just pulling you into a bear hug, this groove is so strong, yet there’s great freedom. “Mel Brown, in a very different way, is an incredible experience to play with,” Pain continues. “He’s just snap-crackle-pop, this incredible, crisp, sophisticated groove that he has. It’s kind of like playing with Mel is like driving in a Cadillac, and Bernard is like hopping aboard a train. They’re both a pretty cool way to travel. And they love each other – they’re a mutual admiration society. “Mel is fearless,” Pain says. “I show up at the gig and I’m noodling with something that I might’ve been practicing at home, and Mel says, ‘What’s that? Let’s do that!’ I say, ‘Mel, I don’t quite know it.’ He says, ‘Aw, let’s just do it.’ I say, ‘I haven’t shown it to the guys.’ ‘Let’s just do it.’ And we do it! And if we get about a minute into it and it’s not happening, he’ll just call another tune and we’ll go right into that. So it’s kind of a fearlessness and a confidence that we can get out of any situation that we get ourselves into, which allows something to happen, as Thara said. And something can happen – something that’s not planned, something that’s magical.” As these and other side projects continued to engage Pain’s attention, it gradually became clear that his time with the Paul deLay Band was coming to a close. “It was like I was getting more and more attracted to doing stuff that was more my musical roots,” Pain acknowledges. “The soul-jazz thing, the soul-blues things, whatever you would call a guy like Howard Tate. [Pain’s set with Howard Tate at the 2002 Waterfront Blues Festival was widely regarded as a standout performance of the weekend.] At the same time I think Paul was missing the kind of stuff he came up playing, like with barrelhouse piano. … It was a pretty amicable parting of the ways; he really wanted to go more to his roots, and he saw that I was also going a different direction musically.” Sweet Baby" James Benton and Louis Pain Pain officially left the deLay Band in January of 2003, leaving him wide open to explore new musical possibilities. The latest of those, his King Louie & Baby James venture, really began eight years ago when Pain met “Sweet Baby James” Benton – who he initially thought was just an ardent fan. “The first time I met James was when I started playing with Mel Brown at Jimmy Mak’s, and James and a couple of older black guys were our ‘Amen Corner,’” Pain says. “They were just so supportive and vocal, and I really think they helped make that scene, the Mel Brown Thursday nights at Jimmy Mak’s, so popular. I think they were a big part of that. They were at this one table all the time, shouting encouragement. And then we’d come offstage, and James would always have something funny and colorful to say, which you couldn’t print in the BluesNotes. You’d hear something as you were walking by him, and say, ‘What did he say?!’” Pain eventually learned that Benton was actually a singer with a long and fascinating history in the Portland jazz and blues scene. After his career as a basketball player with the Chicago Hottentots (a Harlem Globetrotters spinoff) came to an end, Benton ran a legendary after-hours club in Portland in the 1950s. He briefly owned a full-fledged nightclub before being shut down by the city when he wouldn’t submit to what was essentially extortion. He also performed and toured with jazz vocal groups for many years. Pain had his first opportunity to play with Benton when Jay Koder invited Pain to team up with him, Benton and drummer Jeff Minnieweather for some gigs. These dates were successful, and Pain’s appetite for Benton’s soulful singing was whetted. Pain also played intermittently with a group Benton had put together called the Original Cats, which included veteran trumpeter Bobby Bradford, who used to fill in occasionally for Miles Davis; trombonist Cleve Williams, who played with Dinah Washington for many years; and former Louis Prima sideman Bob Hernandez on saxophone. But the more Pain and Benton played together, the more they felt that the time was right for them to form their own ensemble – a feeling encouraged by Tracy Pain and Benton’s girlfriend Cathy Galbraith. When putting together King Louie & Baby James, Pain knew he wanted the best. And fortunately, by virtue of his stellar work in the Portland scene over the last fifteen years or so, he was able to attract exactly that. Pain, Benton, Dammann, Caranto and Jones (and sometimes Scroggins) amount to a musical juggernaut that can’t help but command attention. The band’s collective prowess is well-documented on their just-released CD, Live at the Waterfront Blues Festival 2005, about which The Oregonian’s Marty Hughley comments, “Come around and get some while it’s hot.” Those who attended that performance in person know firsthand how exceptional it was, and this disc certainly does it justice. “I don’t think you can fake that kind of energy,” Pain comments. “Baby James always says that what he cares about is spirit. That’s the word he uses. He’s not interested in technique – how much you know or how fast you can play – it’s all about spirit to him.” To bring the right spirit to his own performances, Pain draws upon the influences of everyone he’s learned from – his musically-inclined brothers, his organ heroes, the prior bandleaders who shaped his musical sensibilities, and the players around him. It should be emphasized that he also benefits from the invaluable support of his flight attendant wife Tracy, who abets his musical exploits in countless ways and even treats visiting journalists to bountiful refreshments. As Louis Pain says, “Portland is an amazing musical scene. I always had heard that there was a high caliber of musicianship up in Portland. I found it to be true – the jazz scene, blues scene, all of it.” Thanks in part to Pain’s own arrival here almost twenty years ago, that scene has continued to grow richer still. – Pat McDougall © 2005 Cascade Blues Association” - Pat McDougal

— Blues Notes

“Washougal man creates musical memories ‘King’ Louis Pain likes playing with the greats and encouraging the next generation By Dawn Feldhaus A local man enjoys playing music in his “man cave” (three-car garage), and he has the support of his neighbors. Louis Pain, a Washougal organist and keyboard player, recalls his first rehearsal in the garage with other members of Soul Vaccination in late June 2011. The band was rehearsing for the Waterfront Blues Festival with Bruce Conte, a guitarist with Tower of Power. “I was concerned about how our new neighbors would react to the noise,” Pain said. “I gave the president of the homeowner’s association a heads up, but still throughout the rehearsal, I was braced for the sound of police knocking on the door. The next day, our neighbors told us that they had indeed had an issue with the volume. Namely, they’d wanted us to open the ‘man cave’ doors and windows so they could hear better.” Pain and his wife Tracy purchased their current home in February 2011, after having trouble finding the kind of home they were looking for in Vancouver. They expanded their search to Washougal to find “a nice neighborhood with a view, plenty of storage and a nice yard for us and the cats.” “Tracy grew up in Kailua, Hawaii, and as a boy I spent my weekends and summer vacations in Point Richmond, Calif.,” Pain said. “Both towns are semi-rural but close to big cities — reminiscent of Washougal. We can’t believe that home prices are as low in Washougal as they are. It is such a beautiful place and only 30 minutes from downtown Portland.” Since moving in, the Pains have thrown several parties that feature jam sessions by musicians and vocalists. Participants have included David K. Mathews, an organist with Santana; Bernard “Pretty” Purdie, a drummer; and Rob Paparozzi, a New Jersey vocalist/harmonica player who has worked with the Blues Brothers and with Blood, Sweat & Tears. Pain, 60, enjoys performing when the music isn’t too “mapped out.” “The Mel Brown B-3 Organ Group never rehearses,” he said. “It’s very spontaneous, but it doesn’t sound like a ‘jam’ due to the caliber of the musicians. When the ‘magic’ happens, we get excited, and the audience feeds off that. Regardless of what we’re going through personally at the time — or what audience members are dealing with — the music lifts us collectively,” he added. “It’s amazing and better than any drug.” When Pain was a young boy, his older brothers Lincoln and Duncan enjoyed hearing a Hammond organ on a record. “I couldn’t pick out the sound myself, but anything that my big brothers thought was cool was cool in my eyes,” Pain said. “When I was in my teens, Duncan played in a band with a Hammond player, reinforcing my interest in the instrument. My mom found a blues organ teacher in the newspaper, and the rest is history.” Pain’s musical training involved the private lessons from blues and jazz keyboard players, starting when he was 16. He also took a few classical piano lessons in his 20s, but he never got serious about it. “To this day, I play mainly by ear,” Pain said. He started performing in front of people when he was 18, in a San Francisco nightclub. Duncan grew up to become a successful songwriter, writing for Robbie Nevil, Paula Abdul and others. Pain said his number one ambition as a young musician was to get good enough to play with great musicians. He includes Purdie and Brown in that group. “They bring things out of you musically that you didn’t think you had in you,” Pain said. “One of my Bay Area band leaders, Jules Broussard, used to advise me ‘keep good musical company.’ That is great advice.” Broussard has performed with Ray Charles and Santana. After moving to Portland in 1986, Pain worked with blues and soul artists including Paul deLay, Curtis Salgado, Lloyd Jones and Linda Hornbuckle. Pain usually performs Thursdays, at 8 p.m., with drummer and band leader Mel Brown and the B-3 Organ Group, at Jimmy Mak’s, 221 N.W. 10th Ave., Portland. There is a $5 cover charge. Their next performance is scheduled for Nov. 29. Pain and saxophonist/vocalist Reggie Houston have performed at HEARTH Wood Oven Bistro, in Washougal, and K’Syrah Catering, Wine and Bistro, in Camas. Their next local performance is scheduled for Saturday, Dec. 22, from 7 to 10 p.m., at K’Syrah, 316 N.E. Dallas St. There is no cover charge. Houston, formerly of New Orleans, played with Fats Domino for more than 20 years, as well as the Neville Brothers and Irma Thomas. For more information about upcoming performances, as well as private lessons and organ clinics and rentals, visit www.louispain.com. ” - Dawn Feldhaus

— Camas-Washougal Post-Record